Handmade: A Tale of Production – Part 1

HANDMADE: A TALE OF PRODUCTION

Part One: That Old Magical Cabinet

by Don Clark

We open on the weary toymaker, Henry. He makes loads of old timey wood toys inside the coolest little workshop that was formerly the cutest little barn. It’s not a barn barn. More like an outbuilding that sheep (or something) lived in.You wouldn’t know that now though. Henry re-outfitted the building decades ago. He heats it in the winter with a pot-bellied stove fueled by shop wood scraps. Handy. Henry had the shortest commute he knew of – about fifty feet. He and his wife lived in an old farmhouse. Their kids were grown

His shop it a cozy little place filled with sunlight, toys, and tools. Some of the tools he’s inherited, but most were picked up at yard sales and the like. He has a professional interest to be sure, but, good grief, he has more rusted hand planes than he’ll ever find the time to restore. Let alone, need. In addition to his power saws, he has four or five dozen handsaws. Maybe six? And let’s be honest here; you can make do when one or two. Henry has a half dozen hand-drills. Like he needs any more help adding to his arthritis.

On top of all this, he’s not even sure what some of the tools are.

That doesn’t matter though. Henry’s chief interest is the tool’s owners and their stories.

Take that saw over there. Some old fella used that saw for thirty years before he was just too old. Then he spent a decade first cupping his ear and saying “WHAT?,” before relenting to the inevitable and just nodding when someone spoke to him.

Then he passed, where his tools, rusted from an untended decade in the garage, were sold at an estate sale. His children and grandchildren holding back tears as they swapped old stories. But the tools don’t look like much, they mostly went unsold. Henry can’t bear to think of those tools being shuttled off for scrap.

He bought all the unsold tools. Henry had to keep those tools in use.

Because he can’t bear to think of his old tools suffering a scrap-yard fate.

This is our toymaker. Making toys for the young folks, some of which have grown up to buy his toys for their young folks.

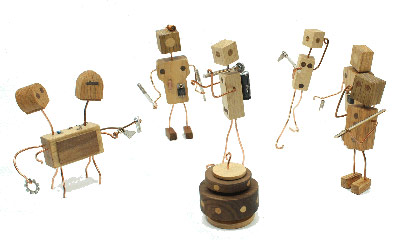

We find him as he’s just hung up the phone, having confirmed his largest order for his most popular toy: The Cosmic Ray 84-T! Zip Zap Zoweey! A real-life walking talking robot!*

* Additional features powered by imagination. (everything is so much cooler with imagination)

The customer was so happy that the order could be completed so quickly. The robot toys would be the perfect reward for the volunteers who’d put in more than 200 hours each restoring the local elementary school. There had been a flood, but the community had rallied together to clean up the building and grounds before the start of the school year. A patron, she explained, had donated a large sum of money for gifts for the volunteers. And what better gifts for cleaning up the school than toys? It was all last minute, and she was thrilled he would be able to fill a large order on such short notice.

Henry didn’t quite follow – he would have six weeks to make five dozen robots. That’s just 10 robots a week. They took a bit of time to make, but not that much time. Throw in his other work and a few other custom orders, it was a easy working time frame.

Is there anything better than knowing what you’ll be doing for the next few weeks? A large order, a set schedule, and – “Oh no.” A shot of cold ran through Henry. He had forgotten what month it was. He had forgotten what month it was! Henry didn’t have six weeks, he had only two. That’s something like thirty robots a week.

But not even that much time. He would have to pack and ship the toys. He had forgotten about transit time too. Oh my gosh. What maybe forty robots a week? Youch! “Is that even possible?”

What is he doing to do?!

“Calm down. Work smart, then hard.” Henry needed to think for a bit. He left his shop and wandered along the stone path back to his house.

His family’s old Victorian farmhouse was amazing. There’s a great porch were you can sip lemonade and whittle away the evening hours. They fixed up the old windmill. It still pumps water. The old silo, however, had to be taken down a few years ago. Even though they had never used the structure, there was still a feeling of loss in Henry.

In a way, our toymaker viewed himself as the last refuge for unwanted “junk”. As if the thought of sending anything to a landfill touched on unresolved childhood issues of loss. Or, so his wife said, for what else could have propelled him to transform their once spacious open attic into a crowded depository of the disused and discarded. The objects with plenty of stories to tell, but with little service remaining to give.

The attic was filled with amazing treasure you never find in any real attic:

A wonderful roll-top desk, gas-light lamps, bureaus, and paintings in gilded frames. Old swords, umbrellas, and brass-tipped wood canes stuffed into a worn out barrel. Great chests filled with silk dresses, funny felt hats, fancy gloves, and shoes so old they walked on dirt roads before cars ever existed. A threadbare couch, a framed pirate treasure map, and a hand-hammered copper ottoman from the Ottoman empire. There were dining chairs built before the franchise had been extended to half of the population. And leather suitcases that had traveled the globe by ship.

Henry turned on one bare light-bulb that brightened the entire space.

The toymaker sat down on the older lounger that Great Aunt Maureen swore Napoleon sat on (please humor her, she’s very fond of the story). “Sigh, ” said the toymaker.

Henry couldn’t call that nice lady on the phone back. She was so happy about the toys. All the volunteers would be happy, she insisted. And Henry liked to make people happy.

It was sort of his job.

With a pad of paper on his lap he began working out a solution to his problem.

Scribble, scribble, write. Even with sixteen hour days it looked near-impossible.

“If I only had help.” However, our toymaker worked alone. To train someone with such short notice . . .

Then he looked up.

On the oak teachers desk between the television with UHF & VHF dials and the nineteenth-century globe was his old wood cupboard. “Hmm.” He stood up, put the pad and pen on the lounger, that Napoleon almost certainly didn’t sit on, and gently touched the old cupboard.

He inherited the cabinet as a boy from his grandfather. The cabinet was eight inches deep and a foot and a half in height and width. It was painted with a base of faded yellow, decorated and highlighted with a swirly peach-colored design that Henry could never figure if it was vines, flowers, or just swirling geometry. Henry blew the dust off and gave the cabinet a good look. “I still can’t figure out what it is.”

His grandfather had given him the cabinet when Henry was a boy. “The lock doesn’t work. The key for it is gone.” His grandfather said. “Don’t try to make it work.”

“Okay grandpa.” Little Henry had said.

“No.” A mindless response wouldn’t do. “You’ll break it if you fool around with the lock. You understand?”

“Okay grandpa.”

Henry soon marked the cabinet as the holding place for his favorite toy figures. He needed to keep them safe from his little brothers and big sister. It would be safer if Henry could make the lock work. They were always taking things that didn’t belong to them.

Then one day when rummaging through his mother’s jewelry box Henry landed on a small brass key.

“Hmm.” If the key worked the lock in his cabinet he could lock it when he wasn’t there and keep his toys safe from snooping hands.

Henry had forgotten his grandfather’s warning. He was little.

That very night he tested the key. It worked! He went to sleep with the knowledge his toys were safe from sticky fingers (literally in the case of his youngest brother – little Joe never used a fork to eat his pancakes).

It is difficult to describe the feelings little Henry experienced the next morning when he opened the locked cabinet to discover that all the toys inside had come to life. There was the metal motorcycle that looked perfect for Steve McQueen. The tin robot, whose painted doodads were now spinning gears, ticking gauges, and glowing power cells. There was the T-Rex that Henry was relieved to see did not breathe fire. And the stone giant. And the little helicopter.

This is how Henry knew that toys were real. Really real.

He had always imagined they were real, in that fantastical heart of hear of his. The trouble was his rational brain.

His rational brain told his heart to study hard, keep his permanent record clean, find a good job, have fun once a year on vacation, and, oh yes, toys weren’t real (as if that last part needed be said).

Though, here they were. The motorcycle zipped around all by itself, except when it slipped on it’s side. Henry would prop him back up, and off he would go again. The tin robot walked and shuffled about, insensibly bleeping and blooping. The helicopter would occasionally lift off into the open air of the bedroom. Even the T-Rex was stomping about, politely, Henry was pleased to see. The stone giant mostly just sat there.

Henry could lock the toys back into the cabinet, open the door, and they were toys again. Repeating the process brought the toys back to life, so to speak.

Unfortunately none of the toys could explain the situation satisfactorily to the boy. He couldn’t communicate with them. They took little notice of him. On his own, young Henry couldn’t make sense of the situation anyway he tried to look at it. The cabinet soon became less fun and more frustration.

Did they need to eat? Were they happy?

Had Henry freed them? Enslaved them?

It was too much responsibility for the boy, too much for his young mind to process. No one he asked could help him.

His grandfather had passed shortly after giving Henry the cabinet. He missed his grandpa. So Henry stopped using it. Unlocked the cabinet a final time and took his inanimate toys out and placed them carefully on a shelf.

In the attic, Henry strummed his fingers on top of the old cabinet. He had made it a hobby to rectify his rational brain’s nagging with his childhood curiosity. He read books, attended lectures and visited every museum he drove near. He learned a great deal. For one thing, he learned that alternate dimensions weren’t just the work of science fiction. Alternate dimensions might be real. Really real.

Infinite realities all laid on top of one another, existing simultaneously in the same physical space, but in different dimension of reality. For everything you’ve ever imagined to be real: every daydream, flight of fancy, every rambling story – those are as real in some other dimension as trees are in our dimension.

Or, this was the best that Henry could figure.

The cabinet, then was a door that bridged two of these realities.

It could be that the cabinet was some work of advanced science stumbled upon by some old-timey carpenter. The carpenter couldn’t figure it, because it was all beyond his means of understanding.

But that didn’t make it inherently bad.

It would be like showing Abraham Lincoln a helicopter; he wouldn’t understand it – it was well beyond anything he knew. Of course it would be irresponsible to give the Great Emancipator the controls. But for a pilot now to fly it? The pilot would understand it all. No worries.

Perhaps it was the same with the cabinet. Or so, Henry had worked out over the years.

“I’ve never forgotten what month it was before.” Hmm. It was a poor excuse to open up the cabinet again, but . . .

But what? Henry strummed his fingers on the cabinet. Practical science? Like Benjamin Franklin and Joseph Priestley. Henry, in good conscious, couldn’t pass on the cabinet without understanding it more. And he wasn’t getting any younger. And the thought of disappointing all those volunteers that fixed up the school was sad. Henry let out a long breath, picked up the cabinet, and headed back to his shop.

In the shop, he put the cabinet down on his work bench.

He needed robot toys, and what better way to make robot toys, than with real life robots? Real life? But none of Henry’s off the shelf toys would do for the cabinet. They needed customization and specialization. They needed imagination to imbue in them unparalleled technical expertise.

“Hmm . . .” Henry poked around his shelves and bins for just the right – “Ah. HA!” The old busted radio! He never had fixed it. Back at the work bench, Henry opened up and took apart that old busted radio. From the circuit boards inside he snipped off microchips, capacitors, transistors, and other bits and bobs he didn’t know the names of. He would transform these parts into sub-algorahtmic logic units, micro-fine motor-control, and transfixing trap-syncs. It was his imagination and mind that would make these little toy bots real.

And the cabinet.

Once all the parts had been attached to the toys Henry stepped back to look at his highly specialized team of robot toy manufacturers. Henry nodded. He could see them clearly in his mind’s eye. A motor control specialist, systems engineer, production supervisor, material specialist, etc., etc. There was even a little toy bot in charge of quality control. He placed them into the cabinet and closed the door. He kept the cabinet key in the wood toolbox his father had made before he was born. Henry loved that toolbox and the tools inside. He only opened it up for special projects.

He found the key and inserted it into the lock. Henry turned the key and heard the click of the mechanics inside. He counted to five, turned the key in the reverse, and opened the door.

And there they were.

As easy as that.

Toy robots brought to life.

“Hello.” Said Henry.